Examining the 2015 World Bank’s Xinjiang Technical and Vocational Education and Training Project

By Remy Hellstern

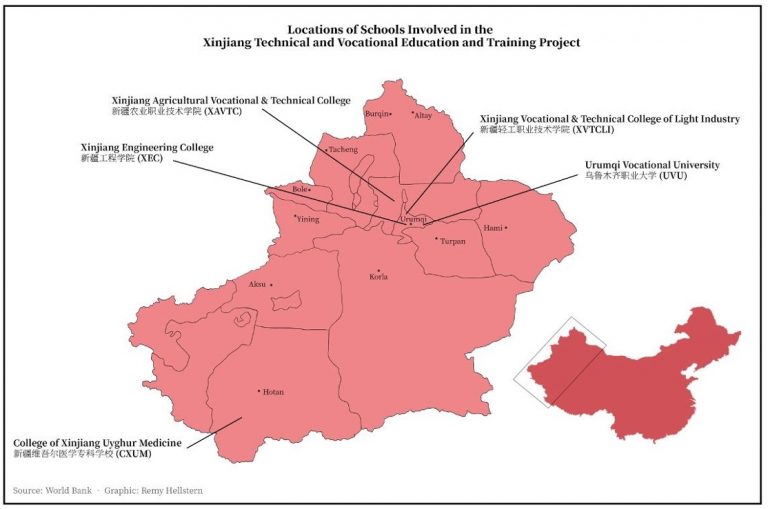

In December 2014, the World Bank introduced a new project entitled, Xinjiang Technical and Vocational Education and Training Project. The expressed goal of this loan was to: usher in school-based reform, strengthen the connection between schools and industry, improve external support for vocational schools, employ high-quality teachers, and upgrade equipment and facilities. This project planned on supplying 50 million USD, between 2015 to 2020, to five vocational schools throughout Xinjiang to encourage ethnic minorities in the region to enroll (World Bank 2014). As part of the Xinjiang Medium and Long-Term Education Reform and Development Plan, the Xinjiang government expressed a keen interest in bolstering educational attainment. Xinjiang has consistently fallen below the national average in educational attainment. For example, the average educational attainment in Xinjiang in 2009 was 9 years whereas the national average was 9.5 years (Ibid). This partnership between the Xinjiang government and the World Bank was seen as an opportunity to remedy that educational attainment gap specifically for minority groups in the region. The project was overseen by the Department of Education of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and implemented in five colleges including Xinjiang College of Engineering, Xinjiang Agricultural Vocational and Technical College, Xinjiang Institute of Light Industry Technology, College of Xinjiang Uyghur Medicine, and Urumqi Vocational University. Figure 1 shows the approximate location of the five schools chosen as part of the World Bank loan and the geographical differences between participating schools.

Figure 1: This regional map shows the location of all 5 schools chosen to be a part of the 2015 World Bank Program.

Source: Xinjiang Technical and Vocational Education and Training Project, World Bank

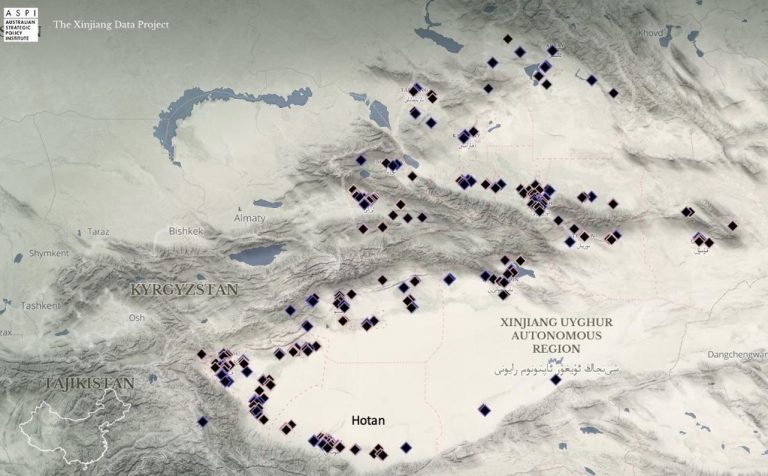

Four out of the five schools chosen to be a part of this program are located in the Northern part of Xinjiang in the counties of Urumqi and Changji. It’s important to note that the Northern region of Xinjiang experienced a decrease in ethnic minorities as a result of the Great Leap West (Liu & Peters, 2017). Whereas the one other school, the College of Xinjiang Uyghur Medicine, is located in the Southern region of Xinjiang which saw an increase in ethnic minority groups, specifically Uyghurs. The College of Xinjiang Uyghur Medicine has been scrutinized because of its proximity to re-education camps (Ruser, 2020). Figure 2 identifies re-education camps throughout Xinjiang and specifically in Hotan, the city in which the College of Xinjiang Uyghur Medicine is located.

Figure 2: Figure 2: This map indicates the location of re-education or detention centers identified with satellite imagery and PRC documentation.

Source: The Xinjiang Data Project at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute

It is important to note that just because this College is located near re-education centers does not guarantee that the school is participating in the detention system. However, the proximity did alert researchers to potential conflicts between the World Bank loan and the re-education system. Due to the fact that the South of Xinjiang is a rural region, critics fear that there could be a potential cross-over in faculty between the College and the re-education centers. In a 2020 article from the Diplomat, “Confessions of a Xinjiang Camp Teacher,” readers learn the story Qelbinur Sedik who recounts being forced to teach Chinese at a re-education camp in 2017. Sedik taught Chinese at Number 24 Primary School in downtown Urumqi until she was summoned to townhall where (Ingram, 2020):

“She was told she would be teaching Chinese to ‘illiterates,’ but strangely, for this mission she was made to sign a confidentiality agreement. A secret rendezvous was fixed for March 1, at 7 a.m., where she was told to wait at a bus stop and call a police officer to pick her up”.

Sedik recalls being taken to a four-story building on the outskirts of Urumqi, surrounded by barbed wire and CCTV cameras. Ultimately, she was taken into a classroom and expected to teach individuals extrajudicially detained in the camp system. A similar sentiment was echoed in a 2018 interview with Darren Byler and a teacher from the Kasawan school in Urumchi which received World Bank funding (Byler, 2018). The interviewee mentioned that as early as 2014 that teams from the school were forced to “volunteer” for the “Becoming Families” campaign (fanghuiju) and political education activities in Yarkand. Involving teachers in political campaigns on the ground and teaching programs in re-education centers has raised alarm among scholars. Examples like the ones aforementioned have caused critics to be concerned regarding the crossover of faculty between legitimate schools in Xinjiang and re-education centers. This issue is particularly worrisome in the case of the World Bank loan. While none of the money went directly to these re-education centers, it is possible faculty that worked in both schools and re-education centers received funding from the loan.

Re-education and Vocational Skills Education and Training Centers

Since 2018, the Chinese re-education system has been featured prominently throughout the news cycle (Phipps, 2020). The original stance from the government was that these re-education camps located in vocational skills and education training centers did not exist. The most notable denial of these facilities happened in front of the UN in 2018 when Hu Lianhe, a senior Communist Party official, stated, “There is no such thing as re-education centres in Xinjiang” (Kuo, 2018). Hu Lianhe is one of the party theoreticians for the Second Generation Minzu policy, learn more about his work here. However, this sentiment quickly changed as more evidence was brought to light about the formation and proliferation of re-education centers. In 2019, the official stance on these centers pivoted to acknowledging the existence of the re-education camp system. In a People’s Daily News report, journalists justified the existence of these centers stating, “vocational education and training centers represents an exploration to save those involved in minor violations of the law and eliminate sources of terrorism” (Mu, 2019). The official admission of these centers brought a new wave of scrutiny from global critics and regional scholars. To learn more about the changing PRC narrative surrounding the re-education system in Xinjiang, view our timeline “Official PRC Response to Human Rights Violations“. With this, there was a renewed interest in the 2015 World Bank loan expanding and funding pre-existing vocational training centers in Xinjiang.

PRC citizen and human rights lawyer Shawn Zhang has been tracking the creation of re-education centers throughout Xinjiang and posits an important distinction between vocational schools versus vocational skills and education training centers (Zhang, 2019). Using government tenders, satellite imagery, and construction notices, Zhang argues that vocational schools are legitimate institutions within Xinjiang whereas the “vocational skills and education training centers” are the re-education camps (Batke, 2019). This is an important distinction when examining the implications of the 2015 World Bank loan. As expressed in the loan, the money was only meant to be used in vocational schools and therefore those were the institutions the World Bank would monitor. However, what Zhang’s research brings to light is that there is crossover in personnel and funding between vocational schools and vocational skills and education training centers. This complicated oversight for the World Bank and created a lack of transparency regarding where the funding was truly going. For example, a worker in the World Bank wrote a letter to the organization about concerns they had regarding funding from this project, specifically money going to vocational skills and education training centers. The worker noted that:

“Yarkand Technical School, which is managed by another school as part of the World Bank program, spent about $30,000 purchasing 30 tear gas launchers, 100 anti-riot batons, 400 sets of camouflage clothing, 100 sets of ‘stab-resistant clothing,’ 60 pairs of ‘stab-resistant gloves,’ 45 helmets, 12 metal detectors, 10 police batons, and barbed wire, according to a tender dated November 2018” (Allen-Ebrahimian, 2019: paragraph 5).

While the funding was not directly given from the World Bank to Yarkand Technical School, it highlights a major oversight problem regarding the implementation of the project. In 2019 in a New York Times article about the loan, journalists note that money going to “partner schools”, much like Yarkand Technical School, are not coming directly from the World Bank and therefore are not monitored (Rappeport, 2019). This complicated chain of command, specifically surrounding who is responsible to oversee where funds are directed, is a troubling development for an agency like the World Bank which is investing a large amount of money into this project. The equipment purchased by Yarkand Technical School indicates a highly militarized school environment that more closely resembles that of re-education centers than traditional schools. Survivors of the re-education camps recount stories of officers using police batons as punishment (Ingram, 2020) and satellite imagery of presumed re-education facilities show buildings surrounded by barbed wire (Samuel, 2018). These accounts match the description of materials acquired by Yarkand Technical School. Yarkand County is located in Kashgar, a majority Uyghur area, as much of Southern Xinjiang is (Toops, 2000). This further indicates that development in the region is focused on minority populations who ultimately have to bear the consequences of the project with little to no consultation. With this in mind, workers at the World Bank and independent researchers raised concerns about the ethics of development aid money going to facilities purchasing security equipment.

World Bank’s Response

In light of the findings surrounding the possible spillover of funding to re-education centres the World Bank issued a statement in 2019 (World Bank, 2019). In this statement the World Bank states they established an internal team to complete a fact-finding mission in which they determined these allegations to be non-substantive. Ultimately the World Bank did not find the evidence presented to be alarming enough to halt the project. However, the World Bank did note that they would be ending the partnership element of the project and they will improve external supervision of the project’s funds. The World Bank does have a history of delaying loans because of human rights abuses. Most notably the World Bank suspended a 90 million USD loan that was supposed to go to Uganda over anti-gay legislation (BBC, 2014). The World Bank did not respond directly to these allegations and completed the project as scheduled in 2020.

References

Allen-Ebrahimian, B. (2019, August 27). The World Bank Was Warned About Funding Repression in Xinjiang. Retrieved from https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/08/27/the-world-bank-was-warned-about-funding-repression-in-xinjiang/

Batke, J. (2019, April 19). What Satellite Images Can Show Us about ‘Re-education’ Camps in Xinjiang. Retrieved from https://www.chinafile.com/reporting-opinion/features/what-satellite-images-can-show-us-about-re-education-camps-xinjiang

BBC. (2014, February 28). World Bank postpones $90m Uganda loan over anti-gay law. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-26378230

Byler, D. (2018). Spirit Breaking: Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City (dissertation). Retrieved from https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/bitstream/handle/1773/42946/Byler_washington_0250E_19242.pdf

Ingram, R. (2020, October 03). Confessions of a Xinjiang Camp Teacher. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2020/08/confessions-of-a-xinjiang-camp-teacher/

Kuo, L. (2018, August 13). China denies violating minority rights amid detention claims. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/aug/13/china-state-media-defend-intense-controls-xinjiang-uighurs

Liu, A. H., & Peters, K. (2017). The Hanification of Xinjiang, China: The Economic Effects of the Great Leap West. Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism, 17(2), 265-280. doi:10.1111/sena.12233

Mu, L. (2019, September 10). Vocational education and training centers in Xinjiang represents new path to address terrorism. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20191214075739/http://en.people.cn/n3/2019/0910/c90000-9613730.html

Phipps, J. (2020, October). “If I speak out, they will torture my family”: Voices of Uyghurs in exile. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/1843/2020/10/15/if-i-speak-out-they-will-torture-my-family-voices-of-uyghurs-in-exile

Rappeport, A. (November, 2019). World Bank Scales Back Project in China’s Xinjiang Region. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/11/us/politics/world-bank-china-uighurs.html

Ruser, N. (2020, September). Exploring Xinjiang’s detention system. Retrieved from https://xjdp.aspi.org.au/explainers/exploring-xinjiangs-detention-facilities/

Samuel, S. (2018, September 18). Internet Sleuths Are Hunting for China’s Secret Internment Camps for Muslims. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/09/china-internment-camps-muslim-uighurs-satellite/569878/

Toops, S. (2000). The Population Landscape of Xinjiang/East Turkestan. Inner Asia, 2(2), 155-170. doi:10.1163/146481700793647797

World Bank. (2014, December). Xinjiang Technical and Vocational Education and Training Project Ethnic Minority Development Plan (pp. 1-11). Project Management Office (PMO). Report number: IPP764 V4

World Bank. (2019, November 11). World Bank Statement on Review of Project in Xinjiang, China. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/statement/2019/11/11/world-bank-statement-on-review-of-project-in-xinjiang-china

Zhang, S. (2019, August 25). Is World Bank Funding Xinjiang Re-education Camps? Retrieved from https://medium.com/@shawnwzhang/is-world-bank-funding-xinjiang-re-education-camps-622b69f7dd14